Bureaucratic oracles at the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) have decreed that 23 million fewer people will have health coverage in 2026 if a House-passed bill to repeal and replace Obamacare were to become law.

As with CBO’s past Obamacare-related pronouncements, corporate and social media sources are uncritically repeating that estimate, overlooking the questionable assumptions that underlie it. A careful reading of the report reveals that the 23 million people that CBO says will join the ranks of the uninsured if the House-passed bill were to become law includes “a few million” who have health insurance. And CBO is sticking with its claim that 14 million fewer people would have Medicaid coverage in 2026, the same conclusion it drew about an earlier version of the House bill. In CBO’s opinion, the fact that the revised House measure spends $46 billion more on Medicaid than the previous one will not result in a single additional person gaining coverage under the program.

The CBO estimate provides a very shaky foundation for policy decisions about health care reform. Those involved in the health policy debates should those estimates with extreme caution because:

- CBO is wrong. Estimating the coverage effects of big and complex legislation is treacherous work and CBO can hardly be faulted for getting it wrong every time. The agency itself acknowledges that its coverage estimates are “especially uncertain.” Guessing how many people will gain or lose coverage under shifting circumstances requires something approaching omniscience. No one can say for sure what sorts of products insurers will offer, what they will charge, what (if anything) relatively healthy people will be willing to pay for a policy, how many people might drop coverage if the tax on the uninsured were repealed.

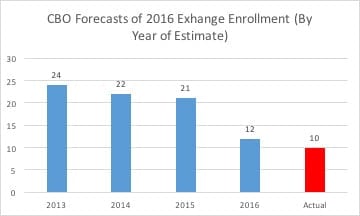

It is curious, though, that CBO’s errors with respect to exchange-based enrollment are not only massive – one of their projections of 2016 exchange-based enrollment was off by 140 percent – but always wrong in the same direction. Time after time, they overestimate exchange-based enrollment. The House-passed bill is measured against these inflated “baseline” coverage numbers, resulting in an erroneously high estimate of the number of people who would become uninsured.

For starters, CBO “forecast” in March 2016 that 12 million people would have exchange-based coverage in that year. CMS said that only 10 million people were enrolled in exchange-based coverage in December 2016. So CBO’s most recent baseline for its coverage estimates already is off by 2 million (16.7 percent).

But it gets worse. Although fewer people signed up for exchange-based coverage during the 2017 open season than in 2016, CBO believes that 15 million people are currently enrolled through the exchanges. That would be an increase of 5 million (50 percent) over 2016.

And CBO doesn’t stop there, conjecturing that exchange-based coverage will jump to 18 million next year. That would represent an improbable 80 percent increase in enrollment between 2016 and 2018.

At some point, CBO will acknowledge that none of this will happen. Its modus operandi since it began preparing estimates of Obamacare enrollment in 2010 is to assume that people will flock to the exchanges at some point in the future, then to reduce its estimate with each passing year. Here is how their estimates of 2016 exchange-based coverage compare with actual enrollment figures for that year.

Eventually, CBO will adjust its model to reflect the fact that 10 million people had exchange-based coverage last year. But by that point, 2016 will no longer be relevant and the agency will have cranked out inflated coverage estimates for the ever-elusive future.

So when CBO says that 8 million fewer people will have individual coverage in 2018 if the House-passed bill becomes law, bear in mind that its analysts imagine, against all evidence, that 18 million people will have exchange-based coverage in 2018 if that bill does not become law.

Although they say that the House-passed bill will cut non-group enrollment from 18 million to 10 million in 2018, it is far more likely that 12 million people (or fewer) will sign up for exchange-based coverage next year, even if Congress leaves Obamacare untouched. So the presumed 8 million reduction in the number of people with individual insurance looks, for the most part, more like an artifact of inflated coverage estimates than the consequence of Obamacare repeal.

- The CBO estimate of the number of people who would be uninsured under the House bill includes millions of people who would have insurance. In declaring that the House bill would increase the number of uninsured people by 23 million in 2026, CBO says that “a few million of those people would use tax credits to purchase policies that would not cover major medical risks.” The report doesn’t specify a number. Are they counting 3 million people who will use tax credits to purchase insurance as uninsured? 5 million?

Nor do they define what they mean by a policy that “does not cover major medical risk.” They do say that “mini-med” plans, “dread disease” policies, dental coverage, and indemnity policies do not meet their definition of coverage. But the House bill prohibits the use of tax credits to pay for “excepted benefits” policies.[1] Which brings us full circle. Just what does CBO have in mind when it talks about subsidized health insurance coverage that it doesn’t count as health insurance coverage? And just how many people with health insurance does CBO deem to be uninsured?

- CBO’s faith in the power of mandates is misplaced. Erroneous estimates and unanswered questions aside, CBO fervently believes that mandates exert a powerful influence on people’s behavior. How powerful? According to its seers, 4 million people will drop their Medicaid coverage in 2018 if Congress repeals the mandate.

That is a curious finding, since the mandate is enforced by reducing an individual’s federal income tax refund and exemptions are easy to come by. CBO notes that the penalties apply to individuals with incomes at 90 percent of the federal poverty level ($10,854). True, but that individual is entitled to claim a standard deduction of $6,350 and a personal exemption of $4,050 in 2017, leaving her with a federal income tax liability of $45, even in the unlikely event that the individual does not qualify for other, non-health-related tax credits. Even at 138 percent of FPL ($16,643), an individual’s federal income tax liability is only $624, absent other credits.

Moreover, an estimated 43.5 percent of U.S. households paid no federal income tax for 2016, including 16 percent who didn’t bother filing taxes at all. Those non-filers are disproportionately concentrated in precisely the income brackets that qualify for Medicaid. Tax penalties would seem to exert little influence on those who owe little or nothing in taxes and who often don’t bother filing them.

CBO’s estimate that 4 million Medicaid beneficiaries (out of 12 million made eligible for coverage under the program by the Obamacare expansion) would torch their Medicaid cards next year because the tax penalty was repealed is highly improbable. It seems a bit far-fetched that millions of people struggling to get by will refuse free health insurance if Congress scuttled the tax on the uninsured.

CBO also thinks that 2 million people will drop their employer-sponsored insurance in 2018 if Congress repeals that tax. That is at least plausible. People who get health insurance through their jobs generally earn enough to incur a tax liability. If they refuse coverage, their employer is required to report them to the IRS, making a tax penalty more likely. It makes sense that some would drop their insurance if Congress repealed the penalty.

But the decision to drop coverage is not irreversible. Most group health plans include an open enrollment period, during which an individual gets an annual opportunity to sign up for insurance. Someone who drops job-based health insurance one year can enroll in it the next. The law is even more generous with respect to Medicaid enrollees. They can sign up at any time. If they show up at an emergency department, a hospital can enroll them in Medicaid on the spot and bill the government for the cost of their care. Someone who is eligible for Medicaid is never truly uninsured, regardless of how long they wait to enroll in the program.

We’ve already seen one flaw in the estimate that 8 million people will drop their individual health insurance policies if the mandate is repealed. Here’s another: according to the IRS, the penalty has not motivated the vast majority of the uninsured to buy coverage.

The IRS Commissioner earlier this year reported to Congress on the efficacy of the individual mandate for the 2015 tax year. Here’s what he reported:

• 6.5 million uninsured people paid the penalty;

• 12.7 million uninsured people – nearly twice as many – got an exemption from the penalty;

• 4.2 million people ignored the penalty – they simply left the line on the tax form blank; the IRS processed their returns and mailed them their refund checks.

That is a total of 23.4 million uninsured people in 2015 who either paid the penalty, obtained a waiver or simply ignored it. According to the National Health Interview Survey conducted by the Centers for Disease Control, 28.6 million people were uninsured in 2015.

That hardly suggests that the individual mandate has been much of a force in persuading people to buy health insurance. If CBO has it right, then the mandate has had a paradoxical effect on health coverage. It clearly has not influenced the behavior of 23.4 million people who have paid, avoided or ignored it. That suggests that the mandate didn’t accomplish its objective of inducing the uninsured to get covered. Overlooking this reality, CBO continues to imagine repeal of the mandate would have a powerful behavioral effect, resulting in 14 million people dropping their coverage next year. That’s a total of 37.4 million people who either are uninsured despite the penalty or are presumed to be insured only because of it.

It is conceivable that CBO is right about that, of course. But if they are, it would suggest that most people who lacked coverage prior to ACA implementation didn’t really want it. The overwhelming majority either chose not to sign up or enrolled only in response to government coercion.

If that’s true, then a central premise of federal health care reform is wrong. The shared assumption of reform advocates from the Left and Right has been that most of the uninsured wanted coverage but couldn’t get it, either because they couldn’t afford it or because insurers denied them coverage. If instead the government is (rather unsuccessfully) trying to pressure people into buying something they don’t want and don’t feel they need, then that is a very different problem indeed.

It seems far more likely that the individual mandate hasn’t had nearly the behavioral effect that CBO thinks it has had and that its repeal is unlikely to have the outsize consequences the agency envisions.

- CBO’s Medicaid assumptions also are dodgy. Obamacare fundamentally changed the nature and financing structure of the Medicaid program. For half a century, states and the federal government shared the costs of providing medical care to certain categories of poor people – the frail elderly, people with disabilities, children and pregnant women among them. The financial arrangement between the federal government and the states took into account each state’s economic circumstances. The Medicaid reimbursement formula provides that the federal government will bear a greater portion of program costs for states with lower per capita incomes. The theory was that such states would have a greater proportion of low-income people eligible for Medicaid and less fiscal capacity to finance their care. As a consequence, the federal government historically has paid 50 percent of the Medicaid costs for California and nearly 75 percent for Mississippi.

Obamacare changed that. It required states to extend Medicaid coverage to nondisabled, non-elderly, non-pregnant adults with incomes up to 138 of the federal poverty level ($16,643). And it provided that the federal government would pay 90-100 percent of the medical costs incurred by this newly-eligible population. The Supreme Court ruled that Congress could not force states to expand their programs and 19 states so far have chosen not to do so.

The District of Columbia and the 31 states that have enlarged their programs (“expansion states”) shifted 100 percent of the medical costs of this new population onto the federal government in 2014-2016. That percentage declined to 95 percent this year and will fall to 90 percent by 2020, where it is to remain in perpetuity.

The federal government thus has singled out this new class of Medicaid recipients for preferential financial treatment. California, for example, must pay 50 percent of the medical costs incurred by a person with developmental disabilities, but only 5 percent of the hospital bills run up by a nondisabled, non-pregnant adult.

Moreover, California gets this favorable cost-sharing arrangement irrespective of its fiscal capacity to provide for its poorest citizens, as measured by the state’s per capita income. This year, the federal government picks up 95 percent of a nondisabled adult’s emergency room visit for Connecticut (per capita income: $71,033), but 70 percent of the cost of providing treatment to a person with developmental disabilities in Alabama (per capita income: $39,231).

The House bill, contrary to multiple reports by corporate news outlets, does not repeal the Medicaid expansion. The federal government will continue to reimburse states that open their Medicaid programs to childless adults with incomes up to 138 percent of the federal poverty level.

The bill does, however, phase out the favorable financial treatment accorded to the nondisabled, non-elderly, non-pregnant Medicaid population. Beginning with those who enroll on or after January 1, 2020, the federal government would bear the same percentage of the medical costs of the expansion population as it does for people that Medicaid long has covered. In New York, for example, the federal government would pay half the costs of insuring a nondisabled adult through Medicaid, the same rate that applies to a child or an elderly nursing home resident in that state.

CBO believes that harmonizing the federal matching rate across eligible populations, coupled with repeal of the individual mandate, would have a devastating impact on Medicaid enrollment. By 2024 and later years, 14 million fewer people would be enrolled in the program, according to CBO.

To understand the magnitude of that reduction, consider that CBO believes that Obamacare’s Medicaid expansion would make an additional 14 million people eligible for Medicaid in 2024. In CBO’s reckoning, retaining the Medicaid expansion while providing more equitable federal matching payments across eligible populations and repealing the individual mandate would wipe out 100 percent of the net coverage effects of that expansion.

To be sure, the House bill also caps the rate of federal Medicaid spending. But that evidently has little effect on CBO’s coverage estimates. An earlier version of the House bill increased per capita Medicaid spending for all eligible populations by the rate of medical inflation (3.7 percent, according to CBO). The baseline rate of per capita Medicaid growth is 4.4 percent, according to the agency. So there would have been a small, but non-trivial reduction in the rate of federal Medicaid spending growth under that version of the bill.

The latest version of the House bill provides a much more generous growth rate for aged and disabled Medicaid recipients. Federal per capita payments would increase by 4.7 percent annually for recipients in those categories and by 3.7 percent for other categories of recipients (e.g., children, pregnant women, childless adults).

The elderly and people with disabilities accounted for a little more than 55 percent of Medicaid spending in fiscal year 2015, according to CMS. But even if only half of Medicaid spending was on behalf of those groups, the average rate of Medicaid spending growth under the House-passed bill would be 4.2 percent, not far below the 4.4 percent rate of growth that CBO projects.

The higher per capita spending growth rate may be one reason CBO now believes that federal Medicaid spending under the bill the House passed would be $46 billion greater than under a previous version of the measure. But this additional money did not alter CBO’s Medicaid coverage estimates. The agency continues to believe that 14 million fewer people will have Medicaid coverage than under current law in 2026. The additional $46 billion in Medicaid spending had no coverage effects, according to CBO.

CBO, like me, has no earthly clue how many people may gain or lose coverage under current law or the House-passed bill. Their impressions, like mine, are based on arguments that some find persuasive and others do not. That is not a criticism of the agency, merely a reminder that estimates are not reality. CBO’s coverage forecasts are speculative and, at least when it comes to estimating exchange-based coverage under Obamacare, have proven consistently inflated and unrealistic. Assuming them to be factual distorts the policy process.

Policymakers should recognize the agency’s limitations and debate competing policy proposals on their merits. Those who believe that taxing the uninsured is a good idea should explain why. Those who think the federal government should provide preferential Medicaid reimbursement rates for medical services provided to non-disabled, childless adults should muster their arguments. But these issues should not be decided by an appeal to CBO’s highly unreliable coverage estimates.

Bludgeoning the opposition with CBO numbers does not advance debate. It silences it.

[1] The definition of “qualified health plan” on p. 115 of H.R. 1628 cross-references section 9832(b) of the Internal Revenue Code. That provision, in turn, cross-references section 9832(c) of the IRC, which lists policies that are excluded from the definition of “health insurance coverage.” Section 9832(c) defines “excepted benefits” policies. The House bill does not permit the use of tax credits to purchase “excepted benefits” policies.

Doug Badger is a Senior Fellow at the Galen Institute who has previously served as a senior White House and Senate advisor.