Expect calls in the next coronavirus bill for a massive expansion of hospital capacity in the U.S. with the federal government deciding how many beds to add and where to add them, funded by an enormous influx of inflationary federal spending.

Doug Badger and Norbert Michel of Heritage have written a new paper that explains with data why this is an unquestionably bad idea.

Their paper, “Coronavirus: Policymakers Should Augment Hospital Capacity Where Needed, Not Mandate Permanent Excess Capacity,” explains that while COVID-19 has strained some hospitals temporarily, there is no structural shortage of acute-care capacity in the U.S.

“The distribution is currently heavily concentrated in a small number of states, and among a small number of counties within those states,” Badger and Michel write. In New York, for example, 77% of cases are in the New York City area. The majority of cases in California are concentrated in its three biggest cities.

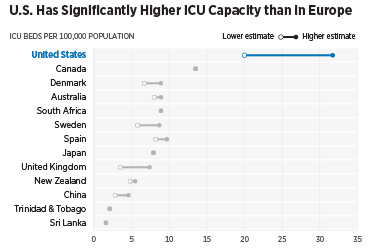

And the U.S. already has two or three times more ICU-bed capacity than European countries (measured by beds per 100,000 population). “…there is good reason to believe that the U.S. health care system is in a better position than most other countries,” they write.

The U.S. does “have fewer inpatient hospital beds per 1,000 population than most other developed countries,” they write. But hospital occupancy in the U.S. is far below average. “[M]ore than one-third of acute-care beds in the U.S. are unoccupied and available to receive new patients…the U.S. already has among the highest excess capacity rates in the world.”

A massive new hospital infrastructure project is not needed. Instead, they call “for something more difficult: the coordination of federal, state, and local officials to address temporary and localized crises…The challenge is to increase capacity on a temporary basis in the areas of greatest need.”

They list more than 20 actions that can be taken, including allowing licensed medical professionals to practice in another state and relaxing scope-of-practice requirements; federal attention to increasing supplies of medical equipment, including stockpiles; preparing to provide auxiliary hospital capacity; and enhancing our ability to do widespread testing, contact tracing, and providing facilities for positive patients to temporarily isolate.

“Policymakers should focus their efforts on forthcoming, localized outbreaks, executing a comprehensive strategy that makes full use of the methods at its disposal,” they conclude.

Read the full paper.